Italian Athenaze — Review

Ἴωμεν Ἀθήναζε! Μετὰ βιβλίου τινὸς Ἰταλίαθεν τὴν γλῶτταν μανθάνωμεν;

Let's go to Athens! Should we be learning the language with a book from Italy?

The heading raises an interesting point and I will in this text briefly touch upon the inadequacy of most Ancient Greek textbooks; though I am using rather strong words, I believe that this point should definitely be addressed so that the teaching — and thus, also learning — of the Ancient Greek language becomes less cumbersome to students.

Why indeed a book from Italy — and in Italian for that matter; though that last statement — the book being in Italian — is only true to a certain extent and I shall more fully explain that shortly. Before I do so, however, I wish to first illustrate how woefully inadequate most Ancient Greek text books really are; or, at the least, how they appear to have a much greater potential than they do presently if only it were to be realised. Ancient languages — though the following statements can be applied to most languages to some extent as well — are in a unique position when it comes to learning language; this is that they are dead. Their being dead obviously complicates matters of teaching it, as there is nobody around whom one may actually speak the language to; and whilst you may indeed speak the language in a classroom setting, this is nowhere near as intensive an experience as actually speaking to a native speaker. Most grammars and textbooks get around this complication — a somewhat nicer way of saying that they outright ignore it — by treating the language as though it never was spoken as a real language was which leads to some further complications; however, these aforesaid latter complications are apparently seen as less severe as the complication of the language no longer being actively spoken. I, however, maintain that the latter complications are much worse indeed.

You may now be wondering what in God’s name I am going on about, so let me try to elaborate; and I must admit that this is not form personal experience per se, but rather mostly from hearsay and you may thus treat my opinions as you see adequate. Nevertheless, you may be aware of the fact that ancient languages are taught in a much different fashion than modern languages are. This is, I believe, obvious to some extent and I do not believe that dwelling on such philosophical questions as What is your name?

, How old are you?

, Where can I find the next bar?

for any length of time is useful in any way, shape or form when it comes to ancient languages. Most people’s goal for learning a (modern) language is being able to communicate to people of other cultures and people whose native language differs from theirs; students of ancient languages tend to be rather apathetic concerning such matters, as obviously this would require a living person to speak to, which is something we appear to be lacking for some bizarre and mysterious reasons.

It should therefore not be surprising to anyone that the study of ancient languages usually revolves around the comprehension of text — prose or poetry — rather than being able to actively communicate in the language. And whilst the comprehension of prose is, I would argue, also a goal for people learning modern languages, it tends to not be their primary goal; their main goal generally being the comprehension of conversations and being able to hold one competently as well.

The traditional and still widely used grammar-translation method involves students studying bulky volumes of grammar and then applying the knowledge learnt by attempting to translate sentences and longer forms of text; rather mundane and, to most pupils at least, rather boring work. It is also a rather unnatural

way of learning a language.

I used to be an advocate of the grammar-translation method, proclaiming proudly my intellectual prowess — or, more accurately, lack thereof — by displaying my knowledge of the grammar of a language I was studying. The rather large downside of this method, however, should have become evident to me as soon as I was either required to read something or, even worse, say something. Indeed, the rather monstrously sized disadvantage of the grammar-translation method is often exaggerated by lack of time; I have, unfortunately, never been able to study a language as if it were my full-time job. If you are able to do so, such as in a summer course, then the grammar-translation method’s disadvantages may not be as evident as they are when you have at most an hour to learn the language each given day (setting aside weekends). For then it becomes rather obvious that spending the majority of the time learning new grammar, translating short texts — as the exercises of textbooks tend to be on the shorter size concerning the length of their texts — and taking notes is a rather inefficient use of one’s time; and, indeed, this may even be the reason for my knowing bits and pieces of a myriad of languages without actually being able to speak them.

Intensively studying grammar leads to one having less time available to read texts in the language and learning vocabulary; obviously an important aspect of learning a language. And, as experience has taught me, people can have the worst grammar you can imagine, but as long as they know a decent amount of vocabulary, you will be able to understand them without too many difficulties. Of course it is vital to know a language’s grammar — I am by no means implying that one can pick up a dictionary of any given language, read and memorise it cover-to-cover and finally know how to speak the language —, but focussing solely (or nearly) on grammar is a most inefficient affair indeed.

It is therefore, I have found, much more time-efficient to, instead, study the language by reading texts — lots of texts. One should read as much as possible, re-reading passages that have already been read until they can be read with confidence. Grammar should, of course, not be neglected; but it should, instead, be introduced in somewhat smaller chunks so that grammar and reading take up about the same amount of time (rather than grammar taking up the majority).

Having gone off on this short tangent, however, I would like to briefly return to my original question: Why use a book from Italy? The answer is that this Italian version of an English textbook is the closest thing we have to an Ancient Greek version of Ørberg’s fantastic Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata which, as the book’s name may have already revealed, attempts to teach Latin by using — Latin itself. This preposterous proposition may indeed be shocking to some and was to me, too; I could not help but laugh at this when I first heard about it. Learning a language? without using a different language? That must be purely some hocus-pocus, a Rosetta Stone in book form (and should you be unaware of Rosetta Stone’s absolutely garbage learning model, I encourage you to look it up yourself as I will not dwell on this matter longer than is necessary)! I appear to have been wrong, however. The English version of this book, by the by, is quite different from the Italian version and does not feature this Ørberg-style approach.

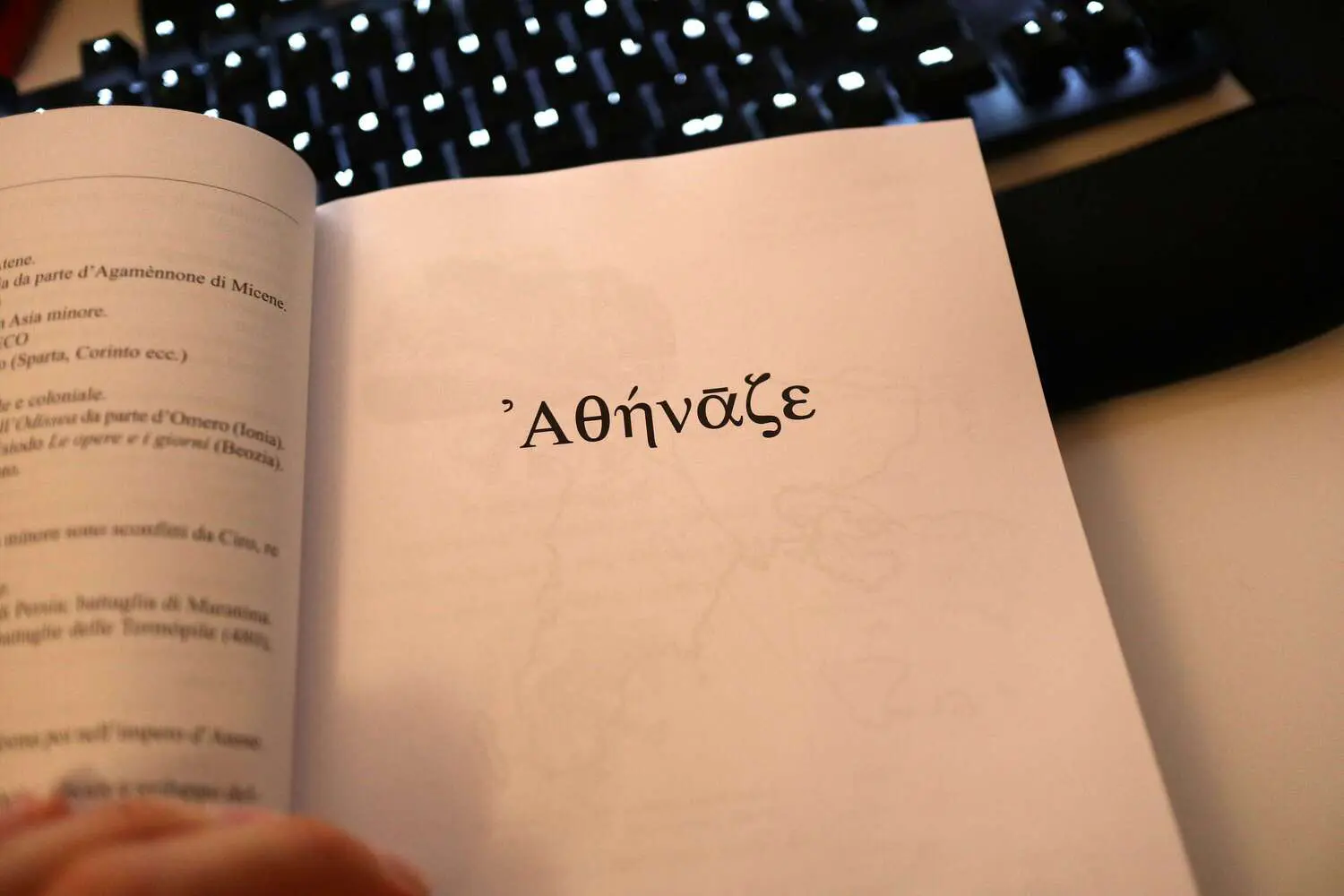

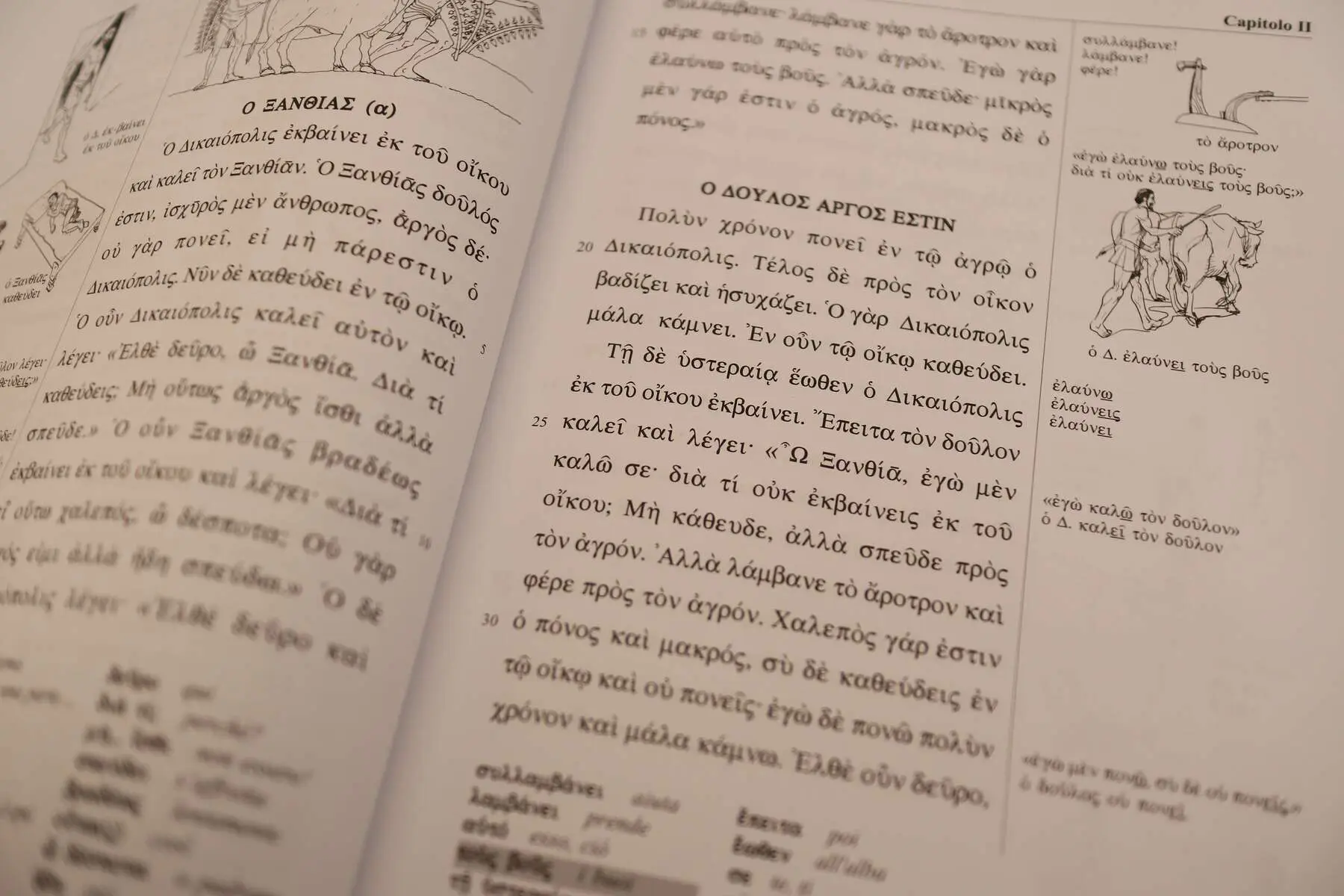

To shoo away those who simply want a quick answer: both absolutely awful and really good. Cryptic answers aside, I am saying this as the Italian Athenaze — which is what this book is called — is a glimpse into what would be possible, a glimpse into a possible future of Ancient Greek textbooks; yet unfortunately this glimpse falls just short of actually achieving what it was meant to achieve. The Italian Athenaze does not actually teach the language in the same way was LLPSI does; it, instead, relies on using Italian on many occasions. It features a large number of margin notes, explaining unknown grammatical concepts and new vocabulary using images and Greek itself, but doesn’t go quite far enough. Additionally, the text that Athenaze is based on (namely the text of the original English version) is quite inadequate for being used in this manner which leads to grammatical concepts and new vocabulary being introduced in a rather strange order and pace when compared to the original LLPSI. It is, however, the only printed and published book that I know of that even comes close to being able to compete with LLPSI.