As mentioned on my page regarding the Nestle-Aland edition of the Greek New Testament, I have found this edition of the GNT an absolutely wondrous way of learning the Greek language — and this can be said, I truly believe, regardless of your religious beliefs. The New Testament, regardless — once again — of what one might think of it, has influenced the Western World in significant ways and reading it in its original language, removing any errors or inaccuracies that might have found their way into the various translations of this text, is quite an interesting experience.

Additionally, reading the original text reveals that the authors of the various books of the New Testament themselves did not natively speak Ancient Greek — at least a large number of them — and, because of that, they unconciously insert constructions of their native (Semitic) languages into their writings which, I find, makes for an interesting reading experience. The various proficiency levels of the authors also shine through, with the author of Luke-Acts usually being credited — I have found — with having one of the most eloquent (and, thus, more difficult) Greek of the New Testament.

I always found, for example, that reading the various Gospels in translation was a rather dry experience, since after having read one of them, you practically knew all the others too, at least when it comes to the style of writing. Reading them in their original, however, somewhat mitigates this problem, as each author has their own, unique way of retelling the story of Jesus' birth, His doings, eventual demise, and resurrection. John's version of the Gospel, for instance, has a very simple writing style and I would go as far as considering it the easiest book of the GNT. Luke's, in turn, is more difficult and eloquent in comparison; all of this makes reading the Gospels much more enjoyable than reading them translated into, for example, German.

Let us now, then, dive into this book and reveal how it is a great way of learning the language.

Whilst the Greek New Testament might, indeed, be written in a comparatively easy to understand manner — compare, for example, the Greek of the NT and Plato —, there are still a myriad of things that a person who is still relatively new to Greek might need help with. Thus, as someone whose Greek is still — at best — in the lower-intermediate area, having a book that helps parse and translate unknown verbs and nouns directly on the page is a most helpful thing. It should thus come as no surprise that I have become an admirer

, so to speak, of this fantastic edition of the GNT — the Greek New Testament.

Parsed vocabulary a page

Parsed vocabulary a pageBut in what manner,

you may ask, is this edition superior to any other?

And it is, indeed, a question well worth asking, considering the fact that there are hundreds — and perhaps, though I did not check, thousands — of different editions of the GNT from various publishers. Therefore, I find it prudent to state that I am by no means claiming this to be the be-all and end-all of all editions of the GNT; rather, I have found it one of the most enjoyable books to read thus far in my, admittedly rather short journey of studying the Ancient Greek language and it all comes down to a mere handful of aspects.

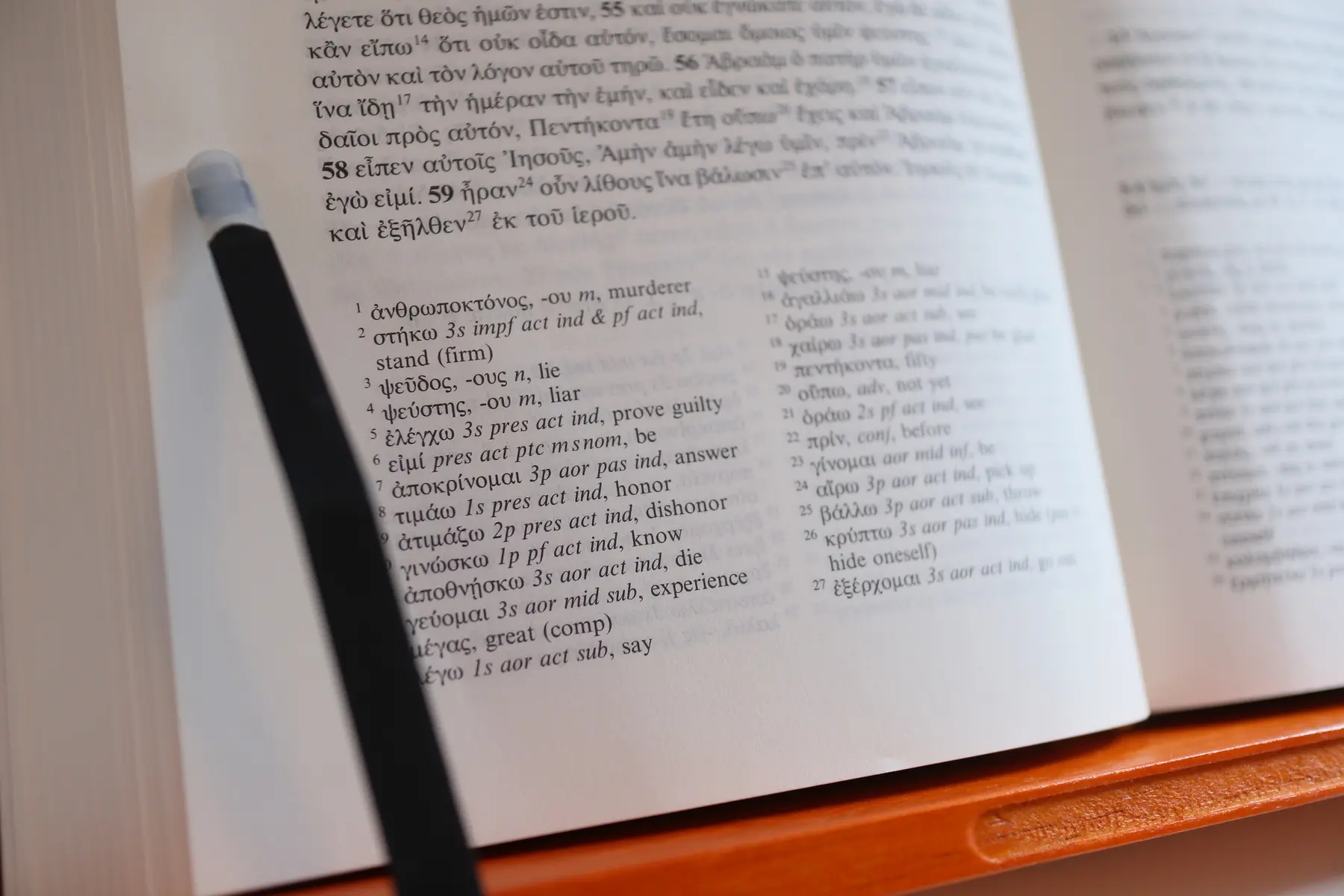

The major reason for my enjoyment of this book is the fact that it parses all vocabulary that occurs less frequently than thirty times in the New Testament at the end of each page they occur in, with words occuring more frequently being found in the dictionary at the end of the book. The verb to parse

has been explicitly chosen as opposed to translate

, not only because the authors of the book, too, use this expression; but mainly because they do not merely translate these words but provide grammatical information for them as well. Let us, for example, take a look at an example from page 280 of the book (John 8:59) and my translation of it: —

ἦραν24 οὖν λίθους ἵνα βάλωσιν25 ἐπ’ αὐτόν. Ἰησοῦς δὲ ἐκρύβη26 καὶ ἐξῆλθεν27 ἐκ τοῦ ἱεροῦ.

They, thus, picked up stones in order to throw them at Him; Jesus at this then hid Himself and left the temple.

This exactly how this verse is rendered in the book — with the exception of the translation, of course —, with the numbers corresponding to a footnote which parses the words as follows: —

24αἴρω 3p aor act ind, pick up

25βάλλω 3p aor act sub, throw

26κρύπτω 3s aor pas ind, hide (pas = hide oneself)

27ἐξέρχομαι 3s aor act ind, go out

It should have now become obvious how this book aids one in the reading of the text; namely by providing contextual translations of words and what role they play in that particular part of the text. There are some people whose posts I have read on various Internet forums that appear to be somewhat opposed to such contextual translations, but I, for one, am quite grateful for them. The Old Testament equivalent of this book (Septuaginta — A Reader's Edition) appears to have somewhat fewer of these contextual translations, from what I have read on aforementioned forums, but I have yet to confirm this.

Another advantage of this edition is that it refrains from the overwhelming number of textual references as, for example, the Nestle-Aland texts contain; and whilst I am aware of why these references exist, as someone who simply wants to read a text and wants to be made aware of, at most, a few major differences between the papyri and scripts, such referenes just make for a nuisance — having half the page be made up of, to me, mysterious scribbles and symbols is a tad annoying.

They are indeed useful for those who wish to do textual criticism of the New Testament, but for someone merely wishing to read they are, at best, annoying. It is, therefore, quite nice to only have a few major differences between manuscripts pointed out from time to time. The authors themselves mention it in their introduction to the book on page 11: —

Compared to the NA28 and the UBS5, the edition at hand focuses on places where variants from the reading of the USB5 significantly impact the meaning of the text. Thus, the number of notes is greatly reduced.

This greatly reduces clutter and enables one to more fully focus on the task at hand — reading the text. It appears that there are still a handful of errors — such as certain glosses being glossed incorrectly —, but the majority is correct.

I believe this is a book which any aspiring learner of Ancient Greek should have upon their bookshelf. The New Testament is an excellent method of acquiring new vocabulary and even — to an extent — improve one’s general Greek reading ability. Indeed, because of the overall simplicity of the text, intermediate students should find the reading of it a breeze. This, in turn, makes the reading of the text a pleasant activity rather than a chore and one which you might find yourself doing for fun.

The book can be picked up, in Germany at least, for €28; a price which I find completely justified, especially considering the fact that a copy of Nestle-Aland’s Novum Testamentum Graece with a German-Greek dictionary cost €38.