Septuaginta: a Reader’s Edition — Review

Ἡ μετάφρασις τῶν Ἑβδομήκοντα

The Translation of the Seventy

In the following article, I will not only be presenting you with information about this particular edition of the Septuaginta, but with general information regarding the Ancient Greek edition of the Old Testament. I will begin by talking about the Septuaginta in general and move on to the analysis of this edition thereafter. Additionally, as this little article has turned into something that I most certainly an unable to call little, I decided to insert a list of contents onto this page. Click any of the links at the top to jump to the particular portion of the page.

Ask any stranger you might find on the street what the Septuaginta is, and the answer would most likely be the real-life equivalent of someone you are chatting to on the Internet sending you a horde of question marks — namely confusion; and this is not only because it is a rather bizarre thing to do — though Jehovah’s Witnesses practice something similar to what I described —, but also because the majority of the population will not have heard about it. Indeed, if one had never heard the word pronounced in English, even its pronunciation might be somewhat of a mystery and its meaning even more so; so what is this book?

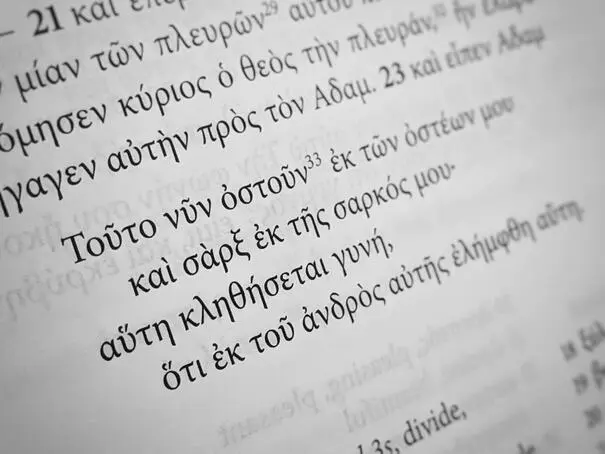

An extract from the early portion of Genesis

An extract from the early portion of GenesisIn very simple — but, nonetheless correct — terms, the Septuaginta merely is the Ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, including the Tanach, the Torah, the Talmud, some Deuterocanonical books and apocrypha. Its name stems from the legend behind its creation, which claims that Ptolemy II Philadelphus, at the request of the librarian of the Library of Alexandria, hired six scholars of each of the twelve Jewish tribes, sent them from Jerusalem to Egypt and had them translate the Bible into Greek. The main source for this legend the Letter to Philocrates, in which the writer of the letter mentions the above-stated claims. Modern-day scholars believe that it was written between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE.

If indeed the aforesaid claims are true — and not everyone believes them to be —, then it would, in my opinion at least, have been a rather strange lot that they had selected. The reason behind my saying so is the fact that the Greek used by the translators to translate the Bible is rather — peculiar. It is, by no means, wrong; but it not at all elegantly translated and, thus, not written in a sophisticated style. There are two theories for this: either the translators were not native Greek speakers; or they were, and the Greek they wrote in is simply the common vernacular of the time.

Another of its peculiarities is the often very literal translation of the Hebrew base text, resulting in sentences you would not generally see in regular Greek. Since explaining this without showing any actual passages would be cumbersome at best, I decided to select a handful and quickly analyse their peculiarities and try to explain them in a manner which even those who do not know the language understand.

Before I begin, I would like to mention a great paper by Jan Joosten of the University of Strasbourg called Varieties of Greek in the Septuagint and the New Testament. Quite a lot of the information will be from this paper. Additionally, I would also like to put a small disclaimer here, saying that I am by no stretch of the imagination an expert at the topics I will be discussing in more detail further below. I simply wish to show you the peculiarities which I discovered during my studies and what I believe their reasons for existing are. If you are more knowledgeable about this topic and find an error or something that needs to be expanded upon, please send me an email, shouting angrily at my stupidity.

Nevertheless, the oft-distinctive nature of the linguistic style used in the Septuaginta is quite intriguing. It bears a strong resemblance to the style used in the New Testament, yet has its own unique features that are not present — or, at least, not present as such — in it. Therefore, even though I would rank the — admittedly subjective — quality of the prose and poetry at a rather low level, its anomalous features present the reader with a Greek that is, most likely, much closer to what the actual people at the time spoke in their day to day lives than that of Plato. I would like to quote a portion of the above-mentioned paper here: –

The ‘Seventy’, it seems, had not studied Greek letters, but wrote the language more or less the way they spoke it. They are never at a loss for a word and are able to vary their language depending on the context. The idiomatic quality of their Greek – although masked to a certain extent by the tendency towards literal translation – suggests native proficiency. But the kind of Greek they know so well is not that of the school, of philosophers and historians, or of the royal court. It is the Greek of the barracks and the marketplace.

— Varieties of Greek in the Septuagint and the New Testament, p. 27

Let us, however, being discussing the aforesaid aspects of the language used in the book. As a result of the aforementioned literal translation — in many aspects, at least — of the Bible, many parts sound odd to someone who doesn’t know the original Hebrew, like myself. We find, for instance, a large amount of verbal duplication — generally a participle in combination with the same verb, conjugated in any of the various verb forms, but frequently in the imperative. One instance of this can be found in Genesis 19:17, where it says the following: —

GRC: καὶ εἶπαν Σῴζων σῷζε τὴν σεαυτοῦ ψυχήν […].

Transliteration: kai eipan Sōzōn sōze tēn seautou psychēn.

Literal: And they said, Saving save your own soul.

NETS: […] [T]hey said,In saving, save your own soul […].

Why exactly this reduplication has been chosen here is, unfortunately, beyond my understanding. As I do not speak any Hebrew at all, I have been looking at a handful of text analyses — especially the one by the BibleHub — and it does not appear as if this verbal reduplication occurs in the base text; most likely, however, the translators back then had a different version of the Hebrew Bible, in which such a reduplication occurs; its main purpose, at any rate, appears to be that of urgency or simply putting more weight onto the command.

Another reduplication that can be found in Genesis 3:16 and in various other places is the following: –

GRC: καὶ τῇ γυναικὶ εἶπεν Πληθύνων πληθυνῶ τὰς λύπας σου καὶ τὸν στεναγμόν σου, ἐν λύπαις τέξῃ τέκνα.

Transliteration: kai tē gynaiki eipen Plēthynōn plēthynō tas lypas sou kai ton stenagmon sou, en lypais texē tekna.

Literal: And to the woman he said Multiplying I will multiply your pain and your groaning, in pains you will give birth.

NETS: And to the woman he said,I will increasingly increase your pains and your groaning; with pains you will bring forth children.

This, once more, appears to be a direct translation from the Hebrew base text. Hebrew appears to use such constructions frequently to, as mentioned earlier, intensify the action that a certain verb implies. A post on Textkit agrees with this sentiment: —

In this case it's a direct translation of the Hebrew, which uses an infinitive absolute as an intensive, הַרְבָּ֤ה אַרְבֶּה֙.

– Barry Hofstetter

There are various other instances in which such duplicate verbs occur and they generally appear to only be used as a type of intensification of the action that the verb describes. I must admit that I was confused upon my first seeing them, but I quickly managed to ascertain their purpose — even without needing to consult someone — and was able to continue reading without any trouble.

Another strange grammatical construction that I had already noticed — albeit to a much lesser extent — in the Greek New Testament is the rather confusing combination of τοῦ (the genitive masculine and neuter article) and an infinitive verb. It is confusing insofar that, as someone who does not have expert knowledge of the Greek of the New and Old Testament, it throws you off-guard and leaves you wondering whatever the author might want to say. It also appears to be a purely Koine phenomenon, as I have yet to stumble across this particular combination in any other dialect of Greek. Indeed, Attic or Ionic might use the genitive article in combination with an infinitive when said infinitive is being used as a nominal — or articular — infinitive in sentences such as ἀντὶ τοῦ μάχεσθαι

(anti tou machesthai, Instead of fighting

); but I highly doubt it can be used in the same manner in which it is used in the Greek Old Testament.

For the usage in the Greek Old Testament reminds me starkly to the Attic purpose clauses introduced of ἵνα

(hina) or ὅπως

(hopōs; ὅκως

, hokōs in Ionic). There might be cases where such a construction was used even it the more classical variants of Greek, but the — admittedly rather small — selection of texts I have thus far read did not contain it. Unfortunately, I cannot find an example of it at present — for, indeed, when you wish to find something, it appears to be a fact of the universe that you will not —, but I will amend this section with a few examples once I have collected some.

Addendum May 20th 2021: After having read a few more pages of the Old Testament, I have finally stumbled across an example for the rather strange usage of τοῦ that I mentioned in the paragraphs above. The passage I am referring to can be found in Genesis 24:20, where it says the following: —

GRC: ὁ δὲ ἄνθρωπος κατεμάνθανεν αὐτὴν καὶ παρεσιώπα τοῦ γνῶναι εἰ εὐόδωκεν κύριος τὴν ὁδὸν αὐτοῦ ἢ οὔ.

Transliteration: ho de anthrōpos katemanthanen autēn kai paresiōpa tou gnōnai ei euodōken kyrios tēn hodon autou ē ou.

Literal: And the man noticed her and was quiet to know if the Lord blessed his road or not.

NETS: Now the man was observing her closely and was keeping silent to learn whether or not the Lord had prospered his journey.

The aforementioned usage of the masculine / neuter genitive singular definite article can be seen here rather clearly, with its meaning being similar to ἵνα. Indeed, replacing the τοῦ in the above-mentioned excerpt with ἵνα would have a similar meaning, though the overall structure of the sentence would have to be change slightly to accodomate the usage of ἵνα. Whether or not this is a regular

feature of Ancient Greek or simply a quirk of the Septuaginta’s frequently out-of-the-ordinary linguistic features, I do not know; I do know, however, that it is a rather interesting usage, especially considering that both τοῦ and to sound alike.

Whilst the majority of the Greek text within this work is, indeed, Greek, the translators did not attempt to translate a handful of words. Why exactly such things occur is, unfortunately, unknown to me. Jan Joosten claims their usage being due to the fact that the translators simply did not know any way of translating the Hebrew word into Greek and decided to simply use the Hebrew one, especially considering that most people would have most likely known its meaning anyway.

These non-translations, however, appear only rarely and it can be, thus, said that it was probably the last resort of the translators; they did not simply transliterate half the Bible. Words that remain untranslated are things such as χερουβιμ

(Cherubim) or μαν

(Manna), amongst various others. They are also generally written without any accentuation or breathing marks, at least in the Rahlfs-Hanhart edition of the Septuagint which the reader I am using at present is based upon.

After having discussed and analysed the Septuaginta itself, let us now turn our attention towards the one and only reader’s edition that exists for it. As I am sure you are aware, I am a fan of reader’s editions of Ancient Greek texts, such as the GNT reader which I have reviewed on the website previously. It should, therefore, not be too big of a surprise to find out that I have finally — after wanting to buy this masterpiece for over half a year — managed to buy Septuaginta: A Reader’s Edition. It was published by both Hendrickson Publishers and the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft (German Bible Society) in 2018. The creators of this work, however, were Gregory R. Lanier and William A. Ross, both of the University of Cambridge. The textual basis is Alfred Rahlfs’ edition of the Septuagint, first published in 1935.

Title page

Title pageIts layout is, in many aspects, very similar to that of the GNT reader I talked about previously, though the size of this reader is, understandably, much greater. It should also be evident, especially once you have looked at the image at the very top of this page, that this edition of the Old Testament comes in two volumes; the first contains Genesis through 5 Maccabees; and the second one contains Psalms through Bel and the Dragon.

And even though a single volume would have been interesting, its sheer bulk would make it nigh-impossible to read comfortably for any prolonged period of time, unless you had the arm strength of a body builder — for, indeed, both volumes together measure in at roughly 3.5 kg (7.7 lbs); though, perhaps, this should be seen as an advantage, as they might be used as dumbbells for your home gym. Additionally, each volume has an approximate thickness of 5 cm (2 in.), making it an object which requires one to have a rather large bag to carry it around.

The latter two facts are, in part, due to the comparatively thick paper. The majority of Bibles tend to have very thin paper so that both the Old and New Testament can be placed inside a single volume which one can carry without too much trouble. This particular set of volumes, however, uses paper at a grammage of 50g/m²; and even though this is much lower than the grammage of your typical office paper — which typically has 80g/m² —, it is, nevertheless, much thicker than the majority of paper found in other Bibles.

Honestly, I personally find this thicker paper very enjoyable to handle, especially considering the fact that many Bibles I own feel quite flimsy, making you afraid that the wrong glance at it would break it immediately. Unfortunately, I do not have the exact grammage for the paper used in the GNT reader, but I find that the paper used in that particular book is slightly thicker than that used in the Septuaginta.

3rd book of the Psalms.

3rd book of the Psalms.The Septuaginta comes in two different bindings, either a blue cloth hardcover — which is the edition that I bought — or a black flexisoft. The binding on my edition — and I am sure it would be similar with the flexisoft — is excellent. The pages are sewn — not glued! —, which makes this an investment that should, hopefully, last more than a few months. This quality, however, does come at a price; this price being roughly €100 when bought new. But considering both the aforementioned paper and binding quality and also the tremendous amount of work that must have gone into the creation of this, I feel that a price as high as this is more than justified.

The typesetting is, as is the rest of this work, magnificent. Prose can be easily distinguished from poetry and the chosen fonts are both large enough and easily readable. What requires some getting used to, however, is the fact that proper names are, unlike in the GNT, written without any sort of accentuation; this appears to be the norm for the Greek Old Testament, though, and not at all a conscious decision of the creators.

The most exciting part of this set of volumes, however, is not the text itself — you could buy a full edition of the Septuagint for less than half of the price of this work —, but rather the excellent apparatus at the bottom of each page.

The creators of this reader’s edition did an excellent job at creating an easy-to-use apparatus; they clearly oriented themselves by the GNT reader I have already mentioned, but did certain things differently — some of these changes are advantageous and others are regrettable. In this chapter, I will be exploring the differences between the two approaches in more detail.

Textual apparatus.

Textual apparatus.Before I begin about the parsing of vocabulary, I would like to, first, take a look at what kind of vocabulary is included within the apparatus; and, once more, they undoubtedly kept those who have used the GNT reader in mind. This is because the apparatus translates words that occur either 100 times or fewer in the Old Testament or 30 times or fewer in the New Testament. Thus, if you have read the NT using the reader I have talked about before, then you only need to learn a few hundred additional words — namely those that occur more frequently than 100 times in the Old Testament — and you are set to go.

One rather stark difference between the two different apparatūs is the repetition of words in the apparatus. Whereas the GNT reader glosses words only once per page — even if they occur more than once on said page —, the Septuaginta glosses them for every occurrence, unless the word appears several times within one paragraph. Thus, if a word occurs thrice on a page, but two of these occurrences are within one paragraph, then the apparatus lists the word twice. Some might call this mere clutter, but considering the fact that you might not immediately remember a new word after your first time seeing it, the repeating gloss is most helpful and allows for much more fluid reading. I, therefore, must say that I actually prefer this method.

When it concerns the parsing of aforesaid vocabulary, however, I find I am somewhat less enthusiastic. I am by no means saying that the parsing provided is inadequate in any way, but it does leave something to be desired when compared to that found in the New Testament reader. The parsing of verbs is virtually identical across the two readers, but nouns and adjectives do lack behind in parsing information quite significantly; and this is, indeed, not an exaggeration, as nouns and adjectives are virtually never parsed at all. This does not present a large problem whatsoever, but the inclusion of parsed nouns (i. e. providing their gender and genetive forms) was very helpful in the NT reader indeed.

Aside from the nouns, adjectives are not parsed either, a matter which is most obvious when it concerns comparatives and superlatives. The GNT reader would, generally, parse a comparative or superlative adjective by giving its base form — i. e. big

— and put either comp.

or sup.

into brackets behind it; the Septuaginta, unfortunately, does not do this.

It would also have been most helpful if prepositions would be glossed including the case that the noun following them take. This way, learning the case a particular preposition takes — or, in the case of many prepositions, cases — and the meaning of them would have much aided in the avoidance of confusion. Nevertheless, as the Septuaginta’s language is — as mentioned previously — rather vulgar, the lack of information regarding prepositions is unlikely to cause significant problems.

Generally, however, the parsing is more than adequate to provide the necessary information to help in the understanding of a sentence. Their goal was not, as far as I can ascertain, to provide complete parsing information, as they believe this is something which the reader should find in a dictionary, instead. Their approach, thus, differs somewhat from that of the New Testament reader, but the outcome — that is, one’s being able to fluently read the text — is virtually identical.

In general, I am most pleased by this edition of the Septuaginta and the few pet-peeves of mine are, generally, so minor that they can be easily ignored. The reader is an excellent method of reading the Greek Old Testament without needing to consult a dictionary and flip through it, making the reading experience much smoother. Indeed, even though my Greek is at best at a low-intermediate level, I am able to read the Old Testament swiftly; I am actually able to read it about as fluently as I am able to read — more complex — texts in Swedish, which I find quite the accomplishment. The latter part is mostly due to the excellent apparatus they have put into their work and I am grateful for the absurd amount of work that has gone into finishing it.