Herodotus’ Histories — A Review

Ἱστορίαι Ἡροδότου

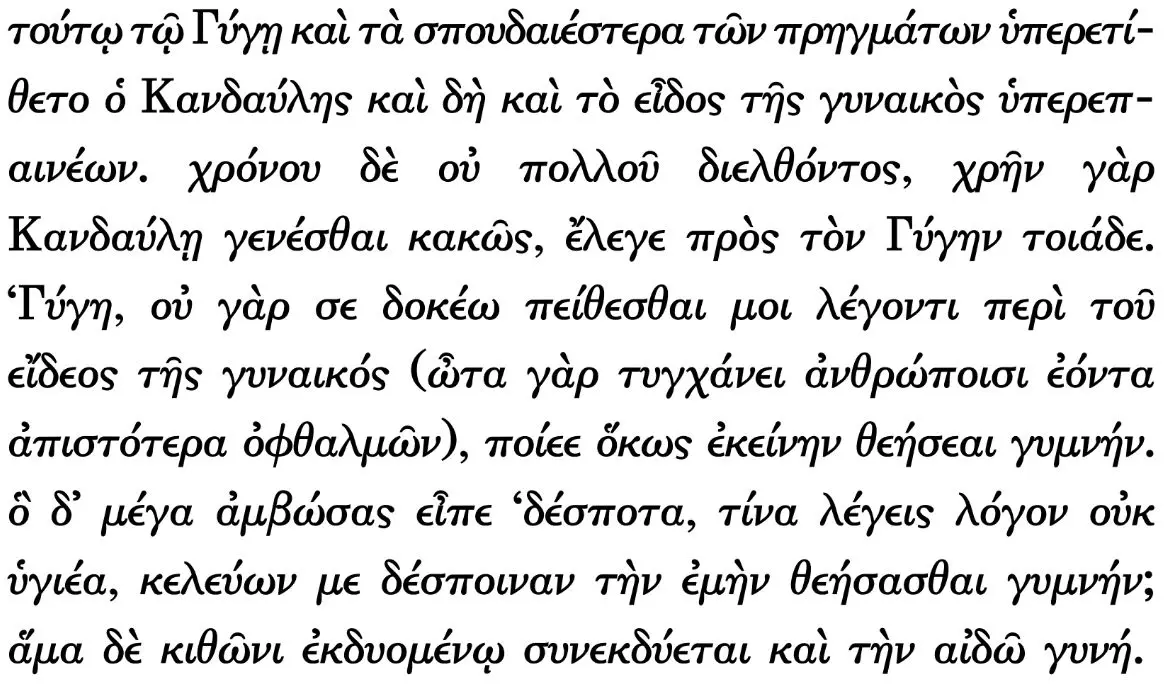

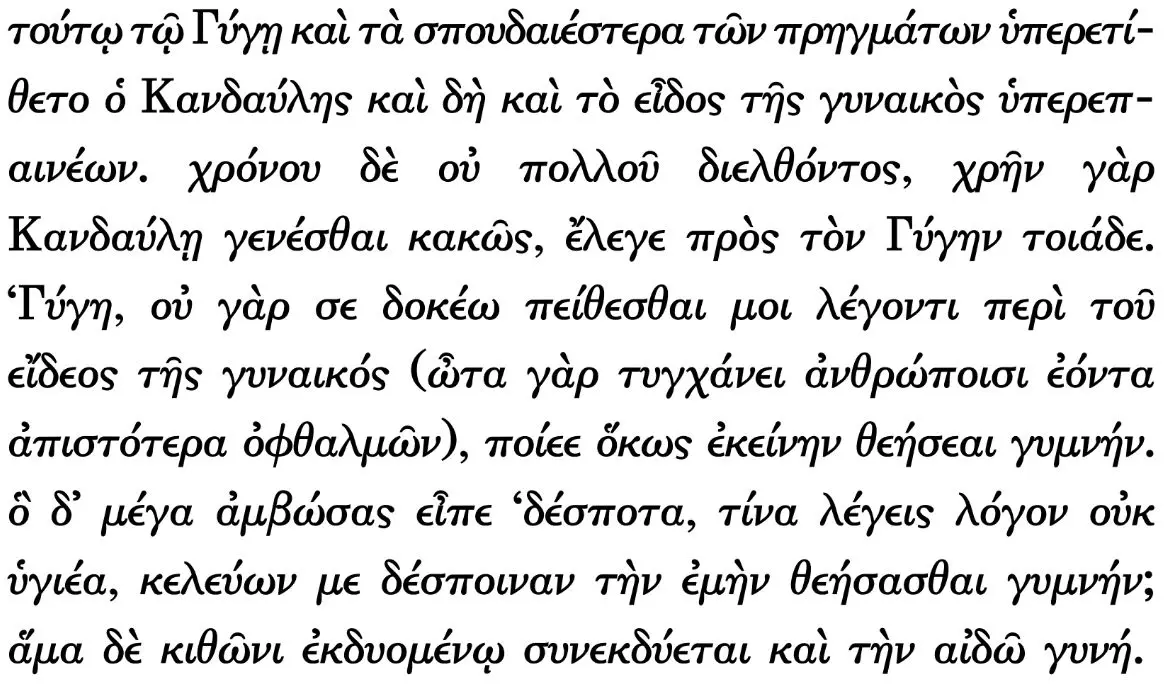

Herodotus’ Histories — circa 450 BC … ὦτα γὰρ τυγχάνει ἀνθρώποισι ἐόντα ἀπιστότερα ὀφθαλμῶν …

… ὦτα γὰρ τυγχάνει ἀνθρώποισι ἐόντα ἀπιστότερα ὀφθαλμῶν …

… ὦτα γὰρ τυγχάνει ἀνθρώποισι ἐόντα ἀπιστότερα ὀφθαλμῶν …

… ὦτα γὰρ τυγχάνει ἀνθρώποισι ἐόντα ἀπιστότερα ὀφθαλμῶν …

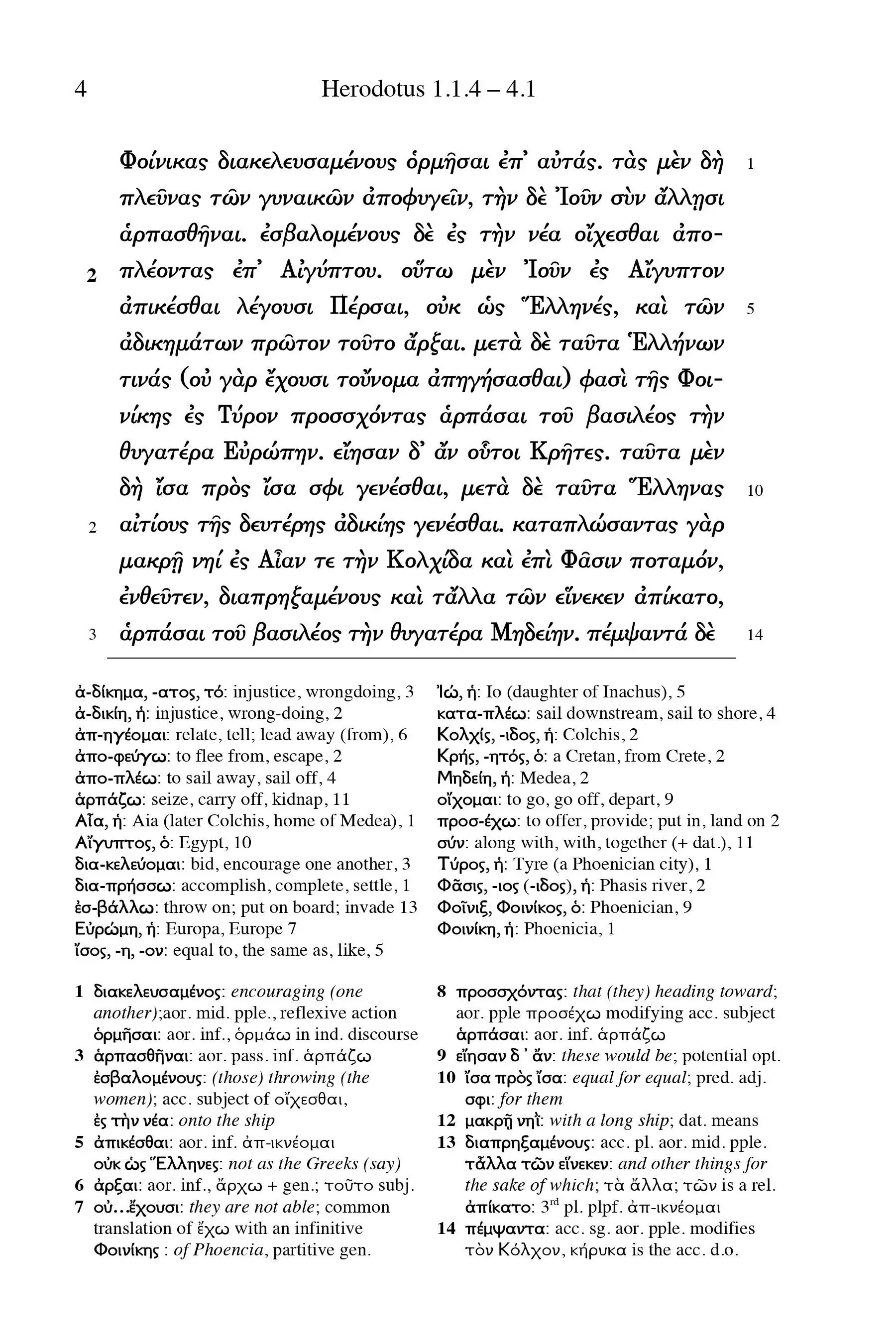

Before I begin talking about the original author of this book and his peculiar dialect, I would like to thank Geoffrey Steadman for creating the edition of this book that I have been using for my study. The image above has been directly taken from one of his books, as well as some of the photos and information regarding the Ionic dialect appearing in the article below. I highly encourage you to use either his freely available PDF version of this book — as I currently am — or, if you have the money, support his work by buying a paperback edition. Please note, however, that this article has not been sponsored, approved or even been seen by him in any way, shape or form; I merely wish to thank the author for creating such great books for intermediate students of the Ancient Greek language.

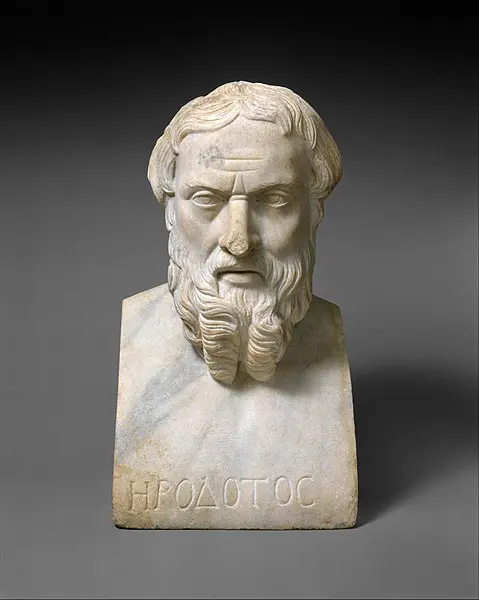

The texts a majority of students of the language begin with are usually written in either Koine or Attic Greek and, though very rarely, Homeric Greek. Interestingly enough, the latter has influences from several dialects, including the dialect we shall be discussing in more detail today — namely Ionic. Herodotus, a historian born in the 5th century BC, is most well known for his work The Histories and is, by a good many, called the Father of History; indeed, the English — and even many other European languages’ — word for, well, history

comes directly from the Ancient Greek word ἱστορία — the plural of which is the title of his work — which translates to something along the lines of inquiry

. And this may not be an unwarranted title, as his work appears to have actually started what we would now call the study of history and even though Wikipedia might not be the best source to quote from, I nonetheless shall do so: —

Moreover, it established the genre and study of history in the Western world (despite the existence of historical records and chronicles beforehand).source

It should, thus, be of no surprise to anyone that a book such as this might be of great importance and, as always, reading it in its original language greatly enhances one’s reading experience. Additionally, his Greek, although different from what most intermediate students are used to — as we shall more fully explore soon —, is of a very simple sort which should be easy enough for an intermediate student to understand with the help of a commentary and perhaps dictionary. Nonetheless, a few people seem to consider Herodotus not worthwhile reading, a sentiment I cannot at all share.

What is it though,

you might now rightfully ask, that makes his writings different?

. To those of you speaking English as their native language, it is perhaps similar in experience as if someone from the UK tried speaking to someone from the US; the language would undoubtedly be the same, though certain words and expressions might not be understood by one of the parties. Additionally, certain things are pronounced differently in one country than they are in another; and so it, too, was in the ancient times. Herodotus’ dialect differs in various ways from the Attic dialect, one of the most prominent features being its changing a good number of long alphas into etas which turns words such as πρᾶγμα and into πρῆγμα.

There are a good number of additional phonetical changes, but there are also a handful of grammatical changes that will definitely throw someone who hasn’t had a lot of exposure to this dialect off at his first seeing it. Many of these, I would argue, can be quite easily and fairly quickly adapted to, such as its relative pronouns (ὅς etc. in Attic) being the same as the articles. It does create some rare occasions wherein you are confused as to the existence of an article in a particular sentence where there should most definitely not be one, when you realise that it is, in fact, the relative pronoun — something that, as a German speaker, I should be used to.

Nevertheless, there are a few changes that would most definitely leave one unaccustomed to this dialect puzzled beyond belief and they mostly revolve around the personal pronouns. A few of the pronoun changes one can easily familiarise oneself with, such as σοί turning into τοι; yet others, such as αὐτῷ/αὐτῇ turning into οἱ, are virtually impossible to guess without having had prior exposure to this dialect. Indeed, the latter often, once more, sparks confusion, as it οἱ not only functions as the nominative masculine singular definite article in Ionic, but also as the dative masculine and feminine singular 3rd person pronoun. Other grammatical changes include the occasional omission of the ἐ- augment and a handful of changes in the declension endings.

All of these differences, although requiring some familiarisation with them, are easily learnt and make for a very interesting and unique reading experience when all you have read up until now was in either the Attic or Koine dialect. It might also serve as a good introduction to the dialect of Homer, who — as mentioned at the beginning of this article — wrote in a dialect that was influenced by, amongst others, Ionic. His sentences are usually short enough and his vocabulary is not too exotic so that your dictionary might not have to be picked up as frequently as it might have to be when reading other authors.

I also find that it helps one realise that Ancient Greek was once, well, not so ancient and that it used to be a language which was spoken across a relatively large area by a diverse group of people who each had their own dialect and way of speaking — just as is the case with virtually all languages on Earth now. It might help one realise that the things you are reading are not written in some strange, alien constructed language but are, instead, the actual thoughts a person who lived over two millennia ago had; but what exactly were these thoughts?

The following are the words with which Herodotus introduces his work and which can be found on the first page of the first book of his Histories. They quite adequately describe his intentions: —

Ἡροδότου Ἁλικαρνησσέος ἱστορίης ἀπόδεξις ἥδε, ὡς μήτε τὰ γενόμενα ἐξ ἀνθρώπων τῷ χρόνῳ ἐξίτηλα γένηται, μήτε ἔργα μεγάλα τε καὶ θωμαστά, τὰ μὲν Ἕλλησι τὰ δὲ βαρβάροισι ἀποδεχθέντα, ἀκλεᾶ γένηται, τά τε ἄλλα καὶ δι᾽ ἣν αἰτίην ἐπολέμησαν ἀλλήλοισι.

What now follows is a presentation by Herodotus of (the city of) Halicarnassus, (written) in the hopes that neither those actions which were done by men (humans in general) may become forgotten with time, nor that those great and wondrous deeds, of which some were performed by the Greeks and others by foreigners, may lose their due fame and glory; and, additionally, what the causes were for their (Greeks and foreigners) waging war against one another.

Herodotus’ goal was a pretty noble one: he simply wished to accurately describe historic events, how they unfolded and what the reasons for their unfolding were, so that aforesaid events won’t, as it would have otherwise happened, vanish from the collective memory of humans, making it appear as if they had never happened in the first place. He appears to have succeeded, too, since, if one may believe what Wikipedia states, his writings are still the primary resource for our understanding of the events during his time: —

Despite the controversy, Herodotus has long served and still serves as the primary, often only, source for events in the Greek world, Persian Empire, and the broader region in the two centuries leading up to his own days. So even if the Histories were criticized in some regards since antiquity, modern historians and philosophers generally take a more positive view as to their source and epistemologic value. source

What may have become evident from the quote above, however, is the fact that Herodotus’ writings are subject to much controversy and many doubt — and have, in the past, doubted — their veracity. One should thus, perhaps, not take his tales as gospel, but one should rather realise that many of the things he wrote about may not have happened exactly as he described them; for, indeed, what story-teller does not enjoy spicing up his stories with a little bit of exaggerated drama? And even if you should doubt his writings’ veracity, you will still be able to enjoy his work — though, perhaps, not as a retelling of actual historic events, but rather as a sort of ancient ἆθλος θρόνων (ἢ γράψωμαι Παιδιὰ θρόνων;).

Indeed, many of the themes to be found in this series of books are easily recognisable and finding parallels for the modern world is an easily accomplished task. Humans, it appears, have not changed much over the course of over two thousand years; our technology may certainly have improved far beyond what Herodotus and those other humans living at the time had or were even capable of conceiving, but human nature has remained pretty much constant over the course of history.

It’s a work filled with greed, hunger for power and needless aggression against other peoples and even war — themes that still very much concern us to this very day. Humans often like to believe themselves to be far superior to those who came before them, spouting not only technological but even moral superiority; and while we truly have — in many areas, at least — advanced far beyond the Ancient Greeks, we still struggle with many of the same problems as they did, being seemingly surrounded by corruption and greed at every level of our existence. Reading this book thus highlights that humans do, indeed, never really change. This, by extension, I find makes one realise that they really were not much different from us and brings one closer to them. As already mentioned, hearing these ancient stories often puts a certain distance between you and he whom you are listening

to (listening to him in your mind, at least); and this distance can, I truly believe, be reduced by realising that what you are reading are real stories — real struggles — which, when adapted, could easily be applied to the modern world.

Reducing this distance even further, then, is accomplished by reading the texts in their original language, far removed from translations that — for no apparent reason — always sound antiquated.

The problem of reading translated texts becomes very evident when you speak both the original language of it and the language it was translated into; and I find it especially noticable with such old texts. Ancient Greek and English, whilst being distantly related, are languages that are quite different grammatically and in terms of vocabulary; translating the vernacular of one language to the other literally often yields results that sound stilted and awkward, just as it would be literally translating German vernacular into English and vice-versa.

I have, thus, always found the reading of ancient texts to be, whilst enjoyable in general, a task that did not bring me any closer to the people who experienced the things which are described in said texts. This often comes down to the translations often sounding far removed from modern times, as translating an ancient text — from another language — often yields such results. But if, instead, you read the original Ancient Greek text, you can virtually hear the people speaking and do not concern yourself with translations which sound antiquated as the text you are reading is literally how the people at the time sounded. I am unsure whether I adequately managed to get across the difference in feeling from reading a translated text from ancient times and the original, but it is truly worlds apart in terms of actual enjoyment and also in terms of closeness to the events which are being described.

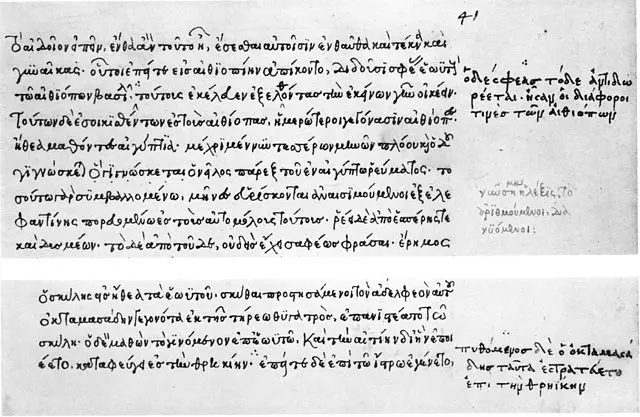

Returning, however, to Herodotus’ Histories: in total, there are nine books of the Histories making it a series of books of considerable length and English translations of his work often border on a length of nearly a thousand pages. The version that I am reading is the reader created by the aforementioned Geoffrey Steadman who, unfortunately, has created readers only for the first and the seventh book of the series — the latter having been in the beta for nearly a decade.

Those who wish to read the entire work in Ancient Greek may want to opt for a bilingual version which has an English translation on one side of a spread of pages and the Greek on the other. The unfortunate problem with such versions is the often very compelling urge to simply glance over to the English version when encountering a passage in the Greek that is not immediately understood and thereby not improving one’s Greek reading ability; a solution to this might be the covering of the English text with an adequately-sized piece of paper. One does not necessarily have to buy such bilingual versions, however, and may, instead, opt to either search the Internet Archive for an old copy — of which there are, I don’t doubt, plenty — or use websites such as sacred-texts.com which, too, offer such versions for free.

All in all, I would most definitely recommend any (lower-)intermediate student of the language — and anyone else who has yet to read it — to begin reading Herodotus’ Histories. It’s filled with fascinating stories and an interestingly different dialect as well, a combination that should make for a rather compelling reading experience.